Dyer Lum

Dyer Lum | |

|---|---|

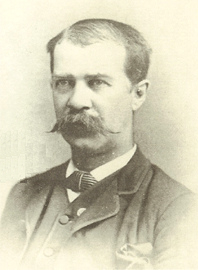

Lum in 1876 | |

| Born | Dyer Daniel Lum February 15, 1839 Geneva, New York, United States |

| Died | April 6, 1893 (aged 54) Bowery, New York City, United States |

| Cause of death | Suicide by poisoning |

| Resting place | Northampton, Massachusetts |

| Years active | 1861–1892 |

| Era | Gilded Age |

| Notable work |

|

| Political party | Greenback Party (1875–1880) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Movement | Labor movement, anarchism in the United States |

| Partner | Voltairine de Cleyre |

| Children | 2 |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anarchism in the United States |

|---|

|

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American labor activist, economist and political journalist. He was a leading figure in the American anarchist movement of the 1880s and early 1890s, working within the organized labor movement and together with individualist theorists.

Born into an abolitionist family, Lum voluntarily enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, in which he fought for the abolition of slavery. After the war, he plied his trade as a bookbinder in New England and became involved in the nascent spiritualist movement, although he soon became skeptical of organized religion and converted to Buddhism. At this time, he became involved in the growing political reform movement, joining the Greenback Party and lobbying for the institution of the eight-hour day, as well as monetary and land reforms.

By the early 1880s, he had become disillusioned by third party politics and moved towards revolutionary socialism and individualist anarchism. He joined the International Working People's Association (IWPA) and the Knights of Labor, within which he advocated for workers organization to push for economic reform and political revolution. Lum was deeply affected by the Haymarket affair, as he was close friends with many of the defendants, including Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer and Louis Lingg, the latter of whom he helped committ suicide in order to avoid execution. Lum's involvement in the affair became a source of criticism from Chicago anarchists, who accused him of displaying a cavalier attitude towards revolutionary martyrdom, as well as the individualist Boston anarchists, who were alienated by his advocacy of revolutionary violence. Lum attempted to use his position to bridge the divide between the two factions, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

After Haymarket, he moved away from advocating violent revolution and became more closely involved in trade union organizing, which he thought provided a means through which to achieve a free association of producers and anarchy. He became an influential figure within the American Federation of Labor (AFL), encouraging its anti-political stance and practice of voluntary association. At this time, he developed a political programme that called for the implementation of mutualist economics through workers' organization and revolutionary tactics. But by the early 1890s, he was overcome by depression and suicidal ideations. He committed suicide in 1893, months before the pardoning of the Haymarket defendants.

Early life and activism[edit]

Family and childhood[edit]

Dyer Daniel Lum was born on February 15, 1839,[1] in Geneva, New York.[2] His paternal family was descended from the Scottish American settler Samuel Lum;[3] and his maternal family were descended from Benjamin Tappan, a minuteman who fought in Massachusetts during the American Revolutionary War, and the father of the abolitionists Arthur and Lewis Tappan.[4] Lum's parents recalled him being a rebellious child, who would often stay up at night to watch storms.[5] Raised in the Presbyterian Church, as a child, Lum became skeptical of religion after he noticed that he had not been struck down for saying "damn" on a Sunday.[6]

Military career[edit]

From an early age, Lum himself joined the abolitionist cause,[7] going on to voluntarily enlist in an infantry regiment of the Union Army after the outbreak of the American Civil War.[8] During the war, he was captured and imprisoned twice by the Confederates,[7] but both times managed to escape.[9] He was then transferred from the infantry to the 14th New York Volunteer Regiment,[10] in which he rose to the rank of captain.[7] At the time, he sincerely believed he was fighting for the abolition of slavery, but he later came to regret that he had risked his life "to spread cheap labor over the South."[11]

Spiritualism, activism and journalism[edit]

Following the end of the war, Lum moved to New England and found work as a bookbinder,[12] a common trade among anarchists of the period.[6] Seeking knowledge about the afterlife, he turned towards spiritualism and wrote on the subjects of science and religion in the journal Banner of Light.[13] Within the spiritualist movement, he came into contact with various associated reform movements, including feminism and socialism. He became an active participant in reform campaigns, participating in the National Equal Rights Party's campaign to nominate Victoria Woodhull for President and petitioning against the declaration of a Christian state.[14]

But by 1873, he had become disillusioned with the superstition of the spiritualist movement, publicly denouncing it and joining the Free Religious Association.[13] In 1875, in search of spirituality outside of organized religion, he converted to Buddhism, which he saw as an egalitarian and humanist philosophy. The Buddhist concept of Nirvana influenced his later turn to revolutionary socialism, as it provided a justification for revolutionary martyrdom.[15]

Political career[edit]

Greenback period[edit]

Towards the end of the Reconstruction era, Lum moved to Massachusetts. [12] At this time, the beginning of the Long Depression brought him into the nascent organized labor movement.[16] He went into politics, joining the Greenback Party[17] and participating in the 1876 Massachusetts gubernatorial election as the running mate of the abolitionist Wendell Phillips.[18] He also served as the private secretary of union leader Samuel Gompers during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.[19]

Lum's political campaigning caused him to lose his job, so in 1878, he moved to Washington, DC in order to continued working as a bookbinder.[20] He also found work as a political journalist,[21] writing articles for Benjamin Tucker's Radical Review[22] and Patrick Ford's Irish World, the latter of which helped him to forge ties between Irish republicans and American workers.[20] In March 1879, he was appointed as a secretary for a congressional committee charged with investigating the "depression of labor."[23] In 1880, he and Albert Parsons were also appointed to a national committee to lobby for the eight-hour day in the United States Congress.[24] But despite their lobbying efforts, Congress was unmoved and their hope for reform started to whither.[25] Lum's experience in national politics got him elected to the executive committee of the Greenback Party, where he pushed for improved labor rights, monetary and land reform, and the establishment of a third party in the United States.[20]

From this position, he took a tour of the country, making a broad range of contacts, including socialists such as Albert Parsons in Illinois, Mormons in Utah and labor leader Denis Kearney in California.[26] From then on, Lum became a convinced anti-capitalist and, drawing from his abolitionist background, began campaigning for the abolition of "wage slavery". He set his sights on the abolition of rent, interest, profit, which he saw as "the triple heads of the monster against which modern civilization is waging war."[27] Lum held the Federal government of the United States responsible, drawing attention to its "class legislation" which had prioritised railroad construction and military training, the latter of which made him consider whether armed revolution would be justified.[28] He momentarily set his sights on the abolition of the two-party system. Although sympathetic to the Republican Party's abolitionist roots, he felt it had since become a party of imperialism and centralized government, while he considered the Democratic Party an unreliable partner for establishing social democracy. He hoped that the Greenback Party could supplant them and realign American politics towards labor reform, but the party's nomination of the Republican James B. Weaver for the 1880 United States presidential election dashed his hopes.[29]

On October 2, 1880, Lum left the Greenback Party, its executive committee and his post at Irish World,[30] and joined the Socialist Labor Party (SLP).[31] But after the failure of both left-wing parties in the 1880 election, they collapsed, with many socialists beginning to move away from reformism and electoralism towards insurrectionary tactics. Revolutionary socialists subsequently broke away from the SLP and established the International Working People's Association (IWPA),[30] which Lum himself joined in 1885.[31]

Conversion to anarchism[edit]

During the early 1880s, Lum was radicalized towards anti-statism, culminating in his adoption of individualist anarchism.[32] In 1882, he published a pamphlet reporting on the federal government's repression of the Mormons' cooperative and voluntary associations,[33] which he argued had been done in order to extend American mining companies' holdings into Utah.[34] His shift to individualist anarchism was inspired by the laissez-faire economics of Herbert Spencer, whose "law of equal liberty" provided him with a basis for Lum's anarchist philosophy and whose advocacy of limited government influenced him to argue against government intervention in labor affairs.[35] He was also influenced by the mutualism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose advocacy of mutual banking inspired the monetary reform policies of many American individualist anarchists, grouped around Benjamin Tucker's magazine Liberty.[36]

In his radicalisation, Lum had pursued both paths that reformers had taken towards anarchism during this period: he rejected reformism in favor of revolution, while also adopting a laissez-faire analysis of wage slavery, respectively acquainting himself with the strategy of anti-state socialism and the ideology of individualism.[37] This "dual path to anarchism" influenced his belief in the necessity for a united anarchist movement, capable of providing a coherent ideology, strategy and organization for the labor movement.[38] Lum considered the time he lived in to have presented a revolutionary situation for anarchists, due to the power vacuum left by the collapse of the left-wing parties, the failure of legislative form and the rapid growth of industrial unions under the Knights of Labor.[39] It was during this time that Lum first developed his anarchist political programme, which advocated for the organization of the working class, a refined revolutionary strategy, and a mutualist economic system.[40]

Anarchist activism[edit]

In 1885, Lum gave infrequent lectures on revolutionary anarchism in New Haven, Connecticut, before moving to Port Jervis, New York. There he joined the Knights of Labor and began writing for a number of anarchist periodicals, including Moses Harman's free love magazine Lucifer,[41] Benjamin Tucker's individualist magazine Liberty[42] and Albert Parsons' collectivist newspaper The Alarm.[43] In Lucifer and Liberty, he called on individualists to support the Knights of Labor and adopt revolutionary politics. While in The Alarm, he wrote frequently about his ideas on workers' organization, revolutionary strategy and individualist economics, while also attempting to link the contemporary labor movement with earlier American revolutionary history.[44]

By this time, popular unrest in the United States was reaching an apex.[45] He predicted that that this wave of unrest would soon erupted into social revolution: "From the Atlantic to the Mississippi, the air seems charged with an exhilarating ingredient that fills men's thoughts with a new purpose."[46]

Haymarket affair[edit]

On May 3, 1886, the Chicago Police Department attempted to shut down a demonstration of striking workers in Haymarket Square. A bomb was thrown from the crowd and the police opened fire back, resulting in several people being killed.[47] Lum quickly responded to the bombing with enthusiastic support, although he also expressed regret that it had only been an isolated, uncoordinated incident.[48] Although the identity of the bomb thrower was never discovered,[49] Lum himself believed the bomb had been thrown by an anarchist, rejecting later "puerile" conspiracy theories that alleged it had been thrown by an agent provocateur.[50]

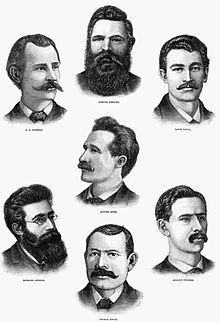

Government repression swiftly followed the bombing, resulting in the closure of The Alarm, Lum's primary platform within the IWPA.[48] Albert Parsons, along with George Engel, Samuel Fielden, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, Michael Schwab and August Spies, were arrested and brought to trial for what became known as the Haymarket affair.[49] Lum sold his bookbinding business in Port Jervis and moved to Chicago in order to support their defense campaign,[51] reviving The Alarm under his own editorship[52] and visiting them in the Cook County Jail on a daily basis.[53] Lum staunchly defended the accused, believing them to have been innocent of the bombing.[54] At the defendants' direction, he compiled the court records and trial transcripts into a book, in which he attempted to demonstrate that they were being convicted for their political beliefs. He also edited their autobiographies, which were published by the Knights of Labor, and organised their defense fund together with the Knights of Labor.[48]

Although no evidence was ever produced of their culpability in the bombing, all eight men were found guilty.[49] When Parsons asked Lum what he ought to do, given the sentence that faced him, Lum responded bluntly: "Die, Parsons."[50] He convinced the sentenced men not to appeal for clemency, as it would "compromise their position".[50] He later claimed that "no one helped them more than I to reject all proffers of mercy."[55]

Lum collaborated with Burnette Haskell, together with whom he planned to unite the IWPA and SLP into a single "American Socialist Federation". But after allegations came out that they were planning to foment a revolution in 1889, on the centenary of the French Revolution, Lum was forced to narrow his strategy.[56] Five days before their execution was scheduled to take place, he wrote in The Alarm that he believed the only thing that could save the Haymarket defendants from their fate would be an act of terrorism.[50] Together with Robert Reitzel, Lum began planning such an attack, intending to blow up the jail in order to free them from their cells.[57] Lum scheduled the attempt to take place on the day before they were due to be hanged. But as the day approached, the prisoners themselves called off the plot, telling Lum that they preferred to die. Lingg told him: "Work till we are dead. The time for vengeance will come later."[58] Despite his desperation, Lum accepted that his comrades were about to die.[56]

On November 10, 1887, Lingg committed suicide with an cigar-shaped explosive he had smuggled into his prison cell.[49] Although journalists Charles Edward Russell and Frank Harris hypothesised that it was Lingg's girlfriend who had smuggled him the dynamite, Voltairine de Cleyre believed it had been brought to him by Lum, recounting this version to her son Harry, who in turn told Agnes Inglis.[59] Inglis didn't believe this version of events and instead hypothesised that it had been prison guards who had killed Lingg, but this counter-narrative was disregarded by Alexander Berkman, as the guards would have known Lingg was about to hang and considered him to have been "the kind of man who'd prefer to die by his own hand."[60] Historian Paul Avrich himself considered it to have been plausible that Lum could have carried this out, "to enable Lingg to cheat the hangman and at the same time enhance his heroic image".[61] Citing Avrich, Frank H. Brooks also considered Lum to have been responsible for enabling Lingg's suicide.[56]

On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Engel, Fischer and Spies were hanged.[49] Lum had been a close friend of all five of the men, who were now considered martyrs of the anarchist movement. After their execution, he published biographies and poems about each of the men, as well as a history book about the affair. He also refused to shake hands with the Knights of Labor leader Terence V. Powderly, who had previously denounced the men as "bombthrowers".[51]

Lum reported that he "shed no tears" for his fallen comrades and wrote that he was glad that the Haymarket affair had taken place.[62] His apparently frivolous attitude towards the affair alienated him from others in the anarchist movement, with Spies' own wife Nina Van Zandt accusing him of "wishing their death", while Johann Most and Lucy Parsons thought him an insensitive "hair splitter".[63] Lum defended himself as having wanted to save "their honor to the cause" and insisted that the defendants had agreed with him.[63] Shortly after the hanging, he wrote to Joseph Labadie: "I am very sorry you take their deaths so hard — can’t you realize that it was nothing but an episode in our work? I do — Perhaps my nearness to them and seeing and feeling their enthusiasm gives me a different feeling."[63] Lum himself actually regretted that he had not himself been with his comrades on the gallows. Union leader George A. Schilling wrote to him that "[t]he trouble is you want to be with Engel, with Spies and Parsons, stand a crown upon your forehead and a bomb within your hand; you want to be a martyr and fill a martyr’s grave."[64]

Regrouping attempts[edit]

Rather than sparking a revolution, the Haymarket affair served to discredit Lum's revolutionary strategy.[65] Benjamin Tucker's individualist group, already suspicious of such a strategy, distanced themselves from the revolutionary socialism of the Chicago anarchists,[66] stressing the differences between it and their own laissez-faire anarchism.[65] Lum thus set out to mend the divide between the individualist and socialist anarchists.[67]

He defended the Haymarket anarchists and challenged Tucker's rejection of revolutionary strategy,[66] resulting in a polemical exchange breaking out between the two, as his position on revolutionary violence only alienated the individualists further.[65] His "middle position" on the issue of private property also drew ideological criticisms.[68] In the pages of Liberty, Victor Yarros called Lum's economic ideas "neither fish nor flesh". Tucker himself described his proposals as "amusing, and at the same time painful", telling Joseph Labadie that he had come to despise Lum. Lum himself returned fire at those contributors to Liberty whom he called the "dung-beetles", denouncing them for their excessive self-interest and lack of care for issues that affected wider society, particularly citing Tucker's defense of strikebreakers, who Lum described as "social traitors".[69]

Meanwhile, the labor movement in Chicago was experiencing an organizational collapse. Despite Lum's protestations, many anarchists retreated into a defensive strategy, with a number of rank-and-file anarchists participating in local elections, while the IWPA itself had effectively dissolved in the wake of the post-Haymarket repression.[65] Despite the diminished influence of The Alarm and the Knights of Labor, Lum attempted to use his positions within both to regroup anarchists around the labor movement. Although he still believed in the inevitability of revolution, he realized that the situation after Haymarket required a different strategy and called for efforts to be refocused towards propagating the principles of anarchist socialism.[70] He opened the columns of The Alarm to anarchists of all political tendencies, while continuing to promote his own ideology as editor. In the paper, he focused on the importance of the labor movement, arguing that the Knights of Labor, through its pursuit of workers' cooperatives and rejection of electoralism, could become a vehicle for an economic revolution.[71]

In early 1888, he began publishing more radical articles, which caused issues with the Post Office and drew increasing levels of police harassment. In June 1888, he moved the printing offices of The Alarm to New York, where he received support from local German anarchists led by Johann Most. There Lum continued printing calls for closer cooperation between the Knights of Labor and the anarchist movement, with articles on the organized labor movement eventually supplanting his earlier focus on mutualist economics, which alienating his remaining individualist readership. By February 1889, the paper had gone bankrupt and ceased publication.[72] Finding himself unable to get his work published in Liberty, Lum began writing for smaller publications like Individualist and Twentieth Century. His attempts to revive the anarchist movement were ultimately unsuccessful, due to pervasive political repression, factionalism and widespread distrust in revolutionary anarchist ideology.[73]

By 1890, Lum's attentions had turned towards the American Federation of Labor (AFL),[74] as he saw its craft unions as vehicles capable of moving society towards anarchism.[73] That year, he published his pamphlet The Economics of Anarchy, which advocated for mutual banks, land reform and workers' cooperatives, and was designed to be read in workers' studies groups.[74] While he continued to believe in the inevitability of revolution, he now discarded revolutionary struggle in favor of union agitation, encouraged by the voluntary cooperation carried out by the AFL's unions in their campaign for the eight-hour day.[75] In 1892, he developed his thoughts into a pamphlet titled "The Philosophy of Trade Unions", which was published by the AFL until 1914. Lum, alongside Joseph Labadie and August McCraith,[75] committed himself to a long-term strategy of influencing trade unions towards anarchist principles.[76] His abandonment of violent revolutionary strategy earned him criticism from Johann Most and other anarchist communists, who accused him of joining a "bourgeois scheme".[77]

Later life and death[edit]

Relationship with Voltairine De Cleyre[edit]

Lum was married and had two children, but later separated with his wife after their children grew to adulthood.[78] In 1888, he met Voltairine de Cleyre.[79] At the time, De Cleyre was in a relationship with Thomas Hamilton Garside, a man who Lum considered to be of a vain and hedonistic character. Lum attempted to warn De Cleyre away from Garside, but the two lovers ran away together; only a few months later, Garside abandoned De Cleyre.[80] De Cleyre was deeply hurt by the rejection and fell into a depression.[81] Lum was there to comfort her and became a stable presence in her life, as "her teacher, confidant and comrade."[78] The two had a lot in common: they both came from New England abolitionist families; they shared a keen interest in essay writing, poetry and translating from the French language; their anarchist philosophy blended individualism and socialism; they were both ascetics and shared sympathy towards the working class and immigrant communities; and they both suffered from mental illness, particularly depression.[82] Lum later wrote to De Cleyre that he had been attracted to her because of her "wild nature".[83]

Although they spent a lot of time apart - Lum living in New York and De Cleyre in Philadelphia - and Lum was 27 years her senior, they came to fall in love with each other.[84] By the following year, Lum was professing his love in poems written to De Cleyre, whom he called "Irene"; De Cleyre herself described her relationship with Lum as "one of the best fortunes of my life".[3] Lum's relationship with De Cleyre was not just romantic, but also "intellectual and moral".[85] De Cleyre's anarchist philosophy developed further under Lum's guidance,[84] inspiring her to reject communist and collectivist anarchism in favor of mutualism and voluntaryism.[86] Lum himself had his hopes for an anarchist future revived by De Cleyre, who inspired him to re-examine individualist anarchism and reconsider his revolutionary startegy.[73] By the early 1890s, Lum and De Cleyre had established an anarchist study group, which grew to include some twenty members.[87] The couple also wrote a social novel together,[88] in which they expounded their social and political philosophy, but it wasn't published during their lifetimes and the manuscript has been lost.[89]

Decline and suicide[edit]

By 1892, Lum had become dissatisfied with his trade union activities, frustrated by his poverty, difficulties with publishers and his long-distance relationship with De Cleyre.[90] At this time, a new cycle of popular protest had broken out, culminating in a series of labor strikes, the largest of which was the Homestead strike. Lum responded by renewing his revolutionary agitation. He gave revolutionary speeches to the Irish Republican Brotherhood, involved himself in bomb plots and organized black miners in Southwest Virginia.[91]

After Alexander Berkman's attempted assassination of the Homestead plant manager Henry Clay Frick, Lum publicly defended the attack,[92] believing it was his duty to "share the effects of the counterblast his action may have provoked".[61] At a public defense meeting in New York, Lum concluded that "the lesson for capitalists to learn is that workingmen are now growing so desperate that they not only make up their minds to die, but decide to take such men as Frick to St. Peter's gate with them."[93] He also smuggled Berkman poison, in case he was sentenced to death; after Berkman was sentenced to 22 years in prison, he initiated a campaign for the reduction of his prison sentence.[61]

By this time, Lum was himself making plans for a violent attack against the ruling class.[94] Lum had written extensively to De Cleyre of his violent ideations, confessing that his anger would frequently consume him until it developed into hatred.[95] He confided to De Cleyre that he planned to carry out a suicide attack to avenge the Haymarket martyrs.[96] De Cleyre herself had come to reject violence and attempted to dissuade him, but Lum responded with derision, calling her "Moraline" and "Gusherine" and sarcastically saying "let us pray for the police here and the Tzar in Russia."[97] He remained determined to fulfill his "pledge" to the Haymarket martyrs, writing to De Cleyre one final time, on February 5, 1892:[98]

I never lost sight of my purpose. I will raise the money and carry out my part of the programme. I am cold, relentless, unflinching. If any fools get in the way, so much the worse for them. In this sentiment cuts no figure. And this time a poster will let people know the 'police' did not do it — as Mrs. Parsons said before. If done, and I think it will work, as we use chemicals, the responsibility will be assumed in posters on the walls.

But Lum never carried out his planned attack, instead falling into a severe depression that left him unable to eat or sleep. Facing poverty, he moved into a flophouse in Bowery. As his insomnia worsened and he became more desperate to get rest,[99] he turned to alcohol and opiates.[100] He also sought refuge in Buddhism, as well as the philosophical pessimism of Arthur Schopenhauer.[90] He briefly attempted to move to his family's home in Northampton, Massachusetts, but under constant financial pressure, was forced to return.[99] One of his friends recalled him, in September 1892, always wearing shabby clothes and carrying a large number of papers, "looking at no one, caring for nothing save the propaganda of Anarchism."[101]

On the night of April 6, 1893, Lum went out for one last walk in New York City,[102] before returning to his bedroom and swallowing a lethal dose of poison.[103] According to De Cleyre, Lum "seized the unknown Monster, Death, with a smile on his lips."[104] In her obituary on Lum, de Cleyre wrote that: "His early studies of Buddhism left a profound impress upon all his future concepts of life, and to the end his ideal of personal attainment was self-obliteration — Nirvana."[105]

Philosophy[edit]

Throughout his life, Lum drastically adapted his political strategy, moving from lobbying and third party politics to anti-political revolutionary activism and trade union organization. He also went through a large ideological evolution, from republicanism and social democracy to revolutionary socialism and individualist anarchism, resulting in his development of an eclectic political philosophy.[106]

Lum's political philosophy synthesised elements from various different foundations within anarchist theory.[107] Lum thought that a successful anarchist movement would require a "convincing and culturally-grounded" critique of political economy, which he proposed in the form of mutualism, and a way of putting such economic reforms into practice, proposing trade union organization and revolutionary strategy.[108] He believed that the formation of a radical labor movement along such lines could attract enough workers that it could become a revolutionary force.[40] Lum also elaborated on the evolutionary ethics that he believed underpinned anarchism, anticipating the later works of Peter Kropotkin.[109]

Lum drew from both American and European political thinkers,[110] including Thomas Paine,[111] Thomas Jefferson, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau from the former,[112] and Herbert Spencer and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon from the latter.[113] Lum's anarchist ideology was grounded in the American radical tradition,[114] rather than imported ideas from Germany or Russia, and he consciously linked his anarchism with what he called the "American idea".[115] Lum's philosophy thus represented a synthesis of American individualism and libertarian socialism.[116]

Mutualist economics[edit]

Lum was inspired by the economic theory of mutualism and defended individual autonomy and voluntary cooperation, outlining his economic views on these matters in The Economics of Anarchy.[117] Lum's own views on mutualism were based in an analysis of "wage slavery" and the reforms that would be necessary to abolish it.[118] While grounding his economic theory in labor issues, Lum applied laissez-faire economic theory to union organizing,[119] drawing from the anti-statism of Thomas Paine and Herbert Spencer, as well as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's critique of political economy, which advocated for mutual banks, land and monetary reform, and workers' cooperatives.[120]

Drawing from individualist economic theory, he argued that labor issues were caused by government-backed monopolies on land and money. He built on Joshua K. Ingalls' land reform policies, arguing that the state-backed land monopoly could be eliminated by abolishing property titles and granting free access to land, which would make renting impossible. He also drew from William B. Greene's monetary theory, arguing that the state-backed monetary monopoly could be ended by establishing mutual banks that could issue their own currency and provide interest-free loans in order to support economic growth.[121] But to Lum, these two reforms were insufficient by themselves; they additionally required the establishment of a free association of producers, which could counter the negative effects of industrialization, while maintaining economic progress and not resorting to a reactionary reversion to artisanal production.[122]

Workers' organization[edit]

Lum adopted the collectivist emphasis on revolutionary organizations as a means to unite the working class and solve the "labor problem".[123] He called for the abolition of wage labor and for anarchists, individualists included, to support unions as a means to achieve the end of the wage system. Lum himself was closely involved in the organized labor movement, as he considered unions to be the best method for workers to combat class stratification and political repression.[124]

Lum's ultimate economic goal was the establishment of a free association of producers, based on cooperative and voluntary principles.[125] In order to achieve this goal, Lum considered it necessary to organize workers within the industrial economy into labor unions,[126] and that the anarchist movement would need to identify itself closely with these organizations. He considered the idea of economic freedom for individual workers to be anachronistic, as workers in an industrial economy rarely produced anything by their own individual labor; he thus concluded that economic freedom could only be achieved through voluntary cooperation between workers. But unlike Marxists or anarchist communists, he did not think that common ownership was an inevitabile consequence of this process, and instead proposed individual ownership of shares within a worker cooperative. His view on workers' cooperation thus synthesised the individiualist view on individual ownership with the collectivist view on collective ownership.[127]

Lum's theory of trade unionism led him to join the Knights of Labor and shape the anti-political and voluntarist practice of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[128] He argued for the Knights to pursue workers' cooperation and avoid electoral participation, hoping that the union could serve as a means to achieve a libertarian economic revolution.[71] He later saw the AFL's craft unions as vehicles for advancing towards anarchy, promoting their voluntarism and supporting their campaign for the eight-hour day, while influencing them to adopt his own economic and political programme.[75] His long-term strategy in this process was to bring trade unions close to anarchist principles.[90]

Revolutionary strategy[edit]

Lum believed in the necessity of a social revolution against all forms of "tyranny and exploitation".[5] Inspired by the methods of the radical abolitionist John Brown, Lum was an advocate of violence, even terrorism, as means to overthrow the state and capitalism.[129] As he thought that the ruling class would only yield power when forced to, he advocated for workers to take up arms against "wage slavery".[130] He also favored propaganda of the deed over agitation, arguing that one event could serve as a better "education" than years of publishing and speechmaking:[95] "Educate the people to grow up to the issue? Nonsense! Events are the true schoolmasters."[46] De Cleyre wrote that Lum's belief in the inevitability revolution was comparable to his understanding of cyclones: "when the time comes for the cloud to burst it bursts, and so will burst the pent up storm in the people when it can no longer be contained"[62]

Eclectic anarchism[edit]

Lum took an eclectic approach to anarchism, coinciding with the principles of anarchism without adjectives and anticipating the later school of synthesis anarchism.[131] Lum believed that economic proposals of different anarchist schools, whether they advocated for collectivism, communism or mutualism, ought to be set aside until they had secured liberty, which he held to be the primary objective of all anarchists, irrespective of economic differences.[132] In the article "Communal Anarchy", Lum proposed that, as such economic arrangements were questions of the future, they must be subordinated to anarchists' shared anti-statist principles until anarchy is achieved.[133] Lum thus advocated for unity between the anarchist movement's socialist and individualist factions, attempting to defend the movement's inherent heterogeneity.[68]

He disliked the "ultra-egoists" that followed the philosophy of Max Stirner, due to their disregard for social problems and defense of strike breakers.[69] He was also staunchly opposed to state socialism,[134] under which he thought would "incompetency will be able to select competency, or capacity to run the social machine."[135] In 1889, he predicted that it would constitute a new form of slavery and necessitate that individualists wage war against the "dependence and collective mediocrity" of the collectivist state.[136] He even criticised Lucy Parsons for adopting the label of "communist".[136]

Legacy[edit]

Tributes[edit]

To Voltairine de Cleyre, Dyer Lum was "the brightest scholar, the profoundest thinker of the American Revolutionary movement."[137] In her eulogy to Lum, written for Twentieth Century on May 4, 1893, De Cleyre wrote that "his genius, his work, his character, was one of those rare gems produced in the great mine of suffering and flashing backward with all its changing lights the hopes, the fears, the gaieties, the griefs, the dreams, the doubts, the loves, the hates, the sum of that which is buried, low down there, in the human mine."[138]

One friend, writing for Liberty on April 15, 1893, said that "in disposition, Mr. Lum was most amiable; in the character of his mind, he was philosophical; in mental capacity, he was at once keen and broad."[139] In a 1927 letter to Joseph Ishill, Emma Goldman wrote that "although he [Lum] seemed dry on the surface I rather think he had considerable depth. He certainly had a beautiful spirit as I am able to testify from my own acquaintance with the man."[5] De Cleyre wrote of his personality that:[140]

Underneath the cold logician who mercilessly scouted at sentiment, underneath the pessimistic poet that sent the mournful cry of the whip-poor-will echoing through the widowed chambers of the heart, that hung and sung over the festival walls of Life the wreathes and dirges of Death; underneath the gay joker who delighted to play tricks on politicians, police and detectives; was the man who took the children on his knees and told them stories while the night was falling, the man who gave up a share of his own meagre meals to save five blind kittens from drowning; the man who lent his arm to a drunken washerwoman whom he did not know, and carried her basket for her, that she might not be arrested and locked up; the man who gathered four-leafed clovers and sent them to his friends, wishing them "all the luck which superstition attached to them"; the man whose heart was beating with the great common heart, who was one with the simplest and poorest.

Historical recognition[edit]

Although Lum is recognized as an important figure in American anarchist history of the 1880s and 1890s, he has largely been referenced in relation to other, more famous, anarchists such as Voltairine de Cleyre, Albert Parsons and Benjamin Tucker.[141] Historian Paul Avrich described Lum as "one of the most neglected and misunderstood figures in the history of the anarchist movement";[142] Frank H. Brooks depicted him as a "late casualty of the Haymarket repression";[93] and Henry David said that Lum was "intellectually head and shoulders above most of the Chicago revolutionaries."[139]

Lum's attempt to bridge the divide between the individualist "Boston anarchists" and the collectivist "Chicago anarchists", as well as his contacts with various immigrant radicals, put him at the centre of the American anarchist movement of the 1880s.[143] Most histories of the American anarchist movement focus on one camp or the other, with historians of the Chicago movement paying little attention to the individualists; while historians of the individualist camp focus largely on tracing intellectual and economic thought, disregarding the collectivists as "violent" and "alien".[144] But Lum's radical activities in several different movements, in different regions, and across two and a half decades, resulted in him also acting as a bridge in the gap of anarchist historiography.[145]

Influence[edit]

The anarchist movement that Lum left behind struggled to keep up with the changing times. Political reforms brought by the Progressive Era made anti-statism less appealing, while the rise of the People's Party and the resurgence of the SLP overtook the movement's anti-electoral strategy.[93] Only two months after's Lum's death, the Haymarket defendants were pardoned by Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld, who ordered the release of Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab from prison.[146]

Inspired by Lum's ecumenical approach to anarchism, in 1893, William and Lizzie Holmes organized an international anarchist conference in Chicago, where they attempted to formulate a common programme for anarchists to unite behind.[147] Lum had previously described the Holmes couple as "two of Chicago's most able and devoted Anarchists."[148] They were joined by Voltairine de Cleyre, Honoré Jackson, C. L. James, Lucy Parsons and William Henry van Ornum, but the conference was boycotted by Benjamin Tucker and Johann Most, who were still locked in an ideological conflict.[147] De Cleyre herself became the most visible proponent of Lum's anarchism without adjectives.[149]

By the mid-1890s, De Cleyre had adopted Lum's mutualist philosophy,[150] synthesising socialism and individualism by advocating for cooperation without state ownership.[151] Lum inspired de Cleyre to expand her philosophical outlook by reading from American, as well as European sources, with Thomas Jefferson's work particularly influencing her approach to anarchism.[152] Although de Cleyre had been a convinced pacifist during Lum's life, by the turn of the 20th century, she had moved closer to Lum's position on revolutionary violence, in some cases seeing it as a justified means to resist capitalism and the state.[153] Lum's maxim that "events are the true schoolmasters" was taken up by De Cleyre following the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, influencing her to support the actions of the Magonistas.[154] In 1902, De Cleyre was shot in an assassination attempt against her. It worsened her physical condition, leaving her in chronic pain for the rest of her life.[155]

Selected works[edit]

Poems[edit]

- "The Needlewoman. A Vision of Prayer in the Nineteenth Century of Christian Civilization" (April 2, 1874, Index)[156]

- "The Evolution of Deity" and "The Supreme Being - Humanity" (January 27, 1876, Index)[156]

- "Wendell Phillips's Grave" (June 20, 1885, Liberty)[157]

- "Harvest" (August 8, 1885, The Alarm)[158]

- "The Alarm" (October 17, 1885, The Alarm)[158]

- "Revolution of 1789" (January 23, 1886, The Alarm)[158]

- "John Brown" (April 3, 1886, The Alarm)[158]

- "You and I in the Golden Weather" (February 1890, Truth)[159]

- "Les Septembriseurs, September 2, 1792" (February 3, 1901, Free Society)[160]

Articles[edit]

- "The Need of Personal Development" (April 29, 1871, Banner of Light)[156]

- "Mental Health vs. Mediumship" (December 21, 1872, Banner of Light)[156]

- "Prognostications" (September 9, 1875, Index)[156]

- "Theism" (November 2, 1876, Index)[156]

- "Buddhism Notwithstanding: An Attempt to Interpret Buddha from a Buddhist Standpoint" (April 29, 1875, Index)[161]

- "Nirvana" and "The Modern Nirvana" (August 1877, The Radical Review)

- "Decoration Day" (May 30, 1885, The Alarm)[162]

- "To Arms: An Appeal to the Wage Slaves of America" (June 13, 1885, The Alarm)[163]

- "A Connecticut Village" (October 31, 1885, The Alarm)[162]

- "Definitions" (November 28, 1885, The Alarm)[164]

- "An Open Letter to a State Socialist" (December 12, 1885, The Alarm)[165]

- "The American Idea" (January 1, 1886, The Alarm)[162]

- "Revolution" (January 23, 1886, Liberty)[166]

- "Rights of Man" (February 6, 1886, The Alarm)[162]

- "Is the Commune a Finality?" (March 6, 1886, The Alarm)[167]

- "Communal Anarchy" (March 6, 1886, The Alarm)[168]

- "Evolution or Revolution" (March 20, 1886, Lucifer)[166]

- "Drift" (March 20, 1886, The Alarm)[158]

- "Inciting to Riot" (May 2, 1886, Lucifer)[169]

- "The Knights of Labor" (June 19, 1886, Liberty)[166]

- "Pen-Pictures of the Prisoners" (February 12, 1887, Liberty)[170]

- "Anarchists Listen to the Siren Song" (April 23, 1887, Liberty)[171]

- "Theoretical Methods" (July 16, 1887, Liberty)[172]

- "Still in the Doleful Dumps" (July 30, 1887, Liberty)[172]

- "The Polity of Knighthood" (February 11, 1888, The Alarm)[173]

- "The Shield of Knighthood" (March 10, 1888, The Alarm)[173]

- "To All My Readers" (April 28, 1888, The Alarm)[174]

- "Correspondenzen" (May 12, 1888, Freiheit)[174]

- "Greeting" (June 16, 1888, The Alarm)[174]

- "The I.W.P.A" (July 14, 1888, The Alarm)[175]

- "Trade Unions and Knights" (July 14, 1888, The Alarm)[175]

- "Powderly's Allies" (October 13, 1888, The Alarm)[175]

- "A Milestone in Social Progress" (September 1889, Carpenter)[176]

- "Collectivist or Mutualist" (March 31, 1890, Individualist)[165]

- "The Social Question" (May 1890, The Beacon)[177]

- "The Fiction of Natural Rights" (May 1890, Egoism)[178]

- "Why I Am a Social Revolutionist" (October 30, 1890, Twentieth Century)[179]

- "August Spies" (September 3, 1891, Twentieth Century)[158]

- "The Social Revolution" (October 24, 1891, The Commonweal)[160]

- "The Basis of Morals" (July 1897, The Monist)[180]

- "Evolutionary Ethics" (July 1899, The Monist)[181]

Books[edit]

- The "Spiritualist" Delusion: Its Methods, Teachings and Effects (1873, Philadelphia)[161]

- Utah and Its People (1882, New York)[182]

- Social Problems of Today (1886, New York)[183]

- A Concise History of the Great Trial of the Chicago Anarchists in 1886 (1886, Chicago)[53]

- The Economics of Anarchy (1890)[184]

- The Philosophy of Trade Unons (1892, New York)[185]

- In Memoriam, Chicago, November 11, 1887: A Group of Unpublished Poems (1937, Berkeley Heights)[186]

References[edit]

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 54; Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 54; Brooks 1993, p. 60; Martin 1970, p. 259.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 54.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 54; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, p. 61.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 54–55; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 54–55; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Brooks 1993, p. 60; Martin 1970, p. 259.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 54–55; Avrich 1984, p. 318.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 54–55; Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 54–55; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Martin 1970, p. 259n89.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 55; Brooks 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 61.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 55; Brooks 1993, pp. 61–62; Martin 1970, p. 259.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 55; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Brooks 1993, p. 62; Carson 2018, p. 109; Martin 1970, p. 259.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 55; Avrich 1984, p. 318; Brooks 1993, p. 62; Martin 1970, p. 259.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 55; Avrich 1984, p. 318.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56; Brooks 1993, pp. 62–63; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56; Brooks 1993, pp. 62–63; Martin 1970, p. 206n24.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 55; Brooks 1993.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 55–56; Avrich 1984, pp. 43, 318–319.

- ^ Avrich 1984, p. 43.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 63.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 64.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 65.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 65; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 65–66; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56; Brooks 1993, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 66.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 67.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, pp. 69–70; Carson 2018, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 75.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 55–56; Avrich 1984, pp. 318–319; Brooks 1993, p. 75; Martin 1970, pp. 243, 259.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 55–56; Avrich 1984, pp. 318–319; Brooks 1993, p. 75.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Avrich 1984, pp. 319–320; Brooks 1993, p. 75.

- ^ a b Avrich 1984, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e Avrich 1978, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Avrich 1978, p. 62.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 59.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 59; Brooks 1993, p. 76; Martin 1970, pp. 259–260.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 59; Brooks 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 62; Brooks 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 62n59.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 65; Avrich 1984, p. 407.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 65.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 62; Avrich 1984, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Avrich 1978, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Brooks 1993, p. 77.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 77; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56; Brooks 1993, p. 77; Carson 2018, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 56.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 78.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 79.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 79; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 79–80; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 259–260.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 53.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 51; Brooks 1993, p. 79; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 52.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 51.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 58.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 97.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 8, 58–59; Brooks 1993, p. 79.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 8, 58–59.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 80.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 64–65; Brooks 1993, p. 81; Carson 2018, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 81.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 61; Avrich 1984, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 66; Avrich 1984, pp. 407–408.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 66.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 67; Avrich 1984, pp. 407–408.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 67; Avrich 1984, p. 408.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 67; Avrich 1984, p. 408; Brooks 1993, p. 80.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 67–68; Avrich 1984, p. 408.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 68–69; Avrich 1984, pp. 408–409; Brooks 1993, p. 81.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 69; Avrich 1984, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 53n51.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 69; Carson 2018, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 74.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 58; Brooks 1993, p. 80.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 155; Brooks 1993, p. 70.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 155; Brooks 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 155.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 66, 72.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 82; Carson 2018, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 82.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 57–58; Brooks 1993, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 71–72; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 72; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 73.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 73; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 73–74; Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 60; Avrich 1984, p. 319; Brooks 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 61; Avrich 1984, pp. 319–320; Brooks 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 151.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 57–58; Martin 1970, p. 260n92.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 260n92.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 53; Brooks 1993, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 69.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, pp. 59–60; Avrich 1984, p. 319.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 57; Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 152.

- ^ Avrich 1984, p. 106.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 111.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 144–145; Carson 2018, p. 111.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f Brooks 1993, p. 61n5.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56n39.

- ^ a b c d e f Brooks 1993, p. 76n48.

- ^ Avrich 1978, pp. 68-69n73.

- ^ a b Avrich 1978, p. 61n55.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 61n6.

- ^ a b c d Brooks 1993, p. 75n46.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 61n56; Brooks 1993, p. 76n48.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 75n45.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 69n30.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 75n47.

- ^ Brooks 1993, pp. 69n30, 75n45.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 152n19.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 76n49.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 76n51.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 77n59.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 77n58.

- ^ a b Brooks 1993, p. 78n61.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 78n63.

- ^ a b c Brooks 1993, p. 79n64.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 79n66.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 259n91.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 80n70.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 61n54.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 58n47; Brooks 1993, p. 80n70.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 58n47.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56n40; Brooks 1993, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 56n40.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 58; Martin 1970, pp. 259-260n91.

- ^ Brooks 1993, p. 80n67; Martin 1970, p. 260n92.

- ^ Avrich 1978, p. 59n50.

Bibliography[edit]

- Avrich, Paul (1978). An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04657-0.

- Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04711-1.

- Brooks, Frank H. (1993). "Ideology, Strategy, and Organization: Dyer Lum and the American Anarchist Movement". Labor History. 34 (1): 57–83. doi:10.1080/00236569300890031. ISSN 0023-656X.

- Carson, Kevin (2018). "Anarchism and Markets". In Jun, Nathan (ed.). Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 81–119. doi:10.1163/9789004356894_005. ISBN 978-90-04-35689-4.

- Martin, James J. (1970) [1953]. "Benjamin R. Tucker and the Age of Liberty". Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827-1908. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher. pp. 202–278. ISBN 9780879260064. OCLC 8827896.

Further reading[edit]

- Brooks, Frank H. (1988). Anarchism, Revolution, and Labor in the Thought of Dyer D. Lum (PhD). Cornell University. OCLC 39696813. ProQuest 8900770.

- de Cleyre, Voltairine (2004) [1893]. "Dyer D. Lum". In Brigati, A. J. (ed.). The Voltairine de Cleyre Reader. AK Press. pp. 147–149. ISBN 1-902593-87-1.

- Johnpoll, Bernard (1986). "Lum, Dyer D. (1839-1893)". In Johnpoll, Bernard K.; Klehr, Harvey (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of the American Left. Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 255–257. ISBN 978-0-313-24200-7.

- McCormick, John S. (1976). "An Anarchist Defends the Mormons: The Case of Dyer D. Lum". Utah Historical Quarterly. 44 (2): 156–169. doi:10.2307/45059577. ISSN 0042-143X.

- Schuster, Eunice (1970). Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism. New York City: Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306718380. LCCN 79-98688. OCLC 165990.

- Tucker, Benjamin, ed. (April 15, 1893). "Death of Dyer D. Lum" (PDF). Liberty. IX (33): 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

External links[edit]

Media related to Dyer Lum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dyer Lum at Wikimedia Commons- Anarchist Library page

- 1839 births

- 1893 deaths

- 1890s suicides

- 19th-century American economists

- 19th-century American newspaper editors

- 19th-century Buddhists

- Abolitionists from New York (state)

- American anarchists

- American anti-capitalists

- American Buddhists

- American Federation of Labor people

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male poets

- American people of Scottish descent

- American political journalists

- American political writers

- American spiritualists

- American syndicalists

- American trade union leaders

- Anarchist writers

- Anarchists without adjectives

- Editors of Illinois newspapers

- Former Presbyterians

- Individualist anarchists

- Knights of Labor people

- Massachusetts Greenbacks

- Mutualists

- Socialist Labor Party of America politicians from Massachusetts

- Suicides in New York City

- Union Army non-commissioned officers