I Was Fired by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. I Wonder Why

10. 10. 2022

/

Muriel Blaive

čas čtení

12 minut

In October 2022, I was fired by

the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, where I had been

working since 2014. Seven of us, out of whom six women, were fired

simultaneously, including two of my former bosses, Blanka Mouralová

and the former ÚSTR director, Pavla Foglová, and the librarian Livia

Vrzalová.

But apparently, I was

the only one from within the research departments to be thrown out.

Here is the update on personnel movement we all received:

I was of course wondering why

I was fired. When I was officially notified, I received this

explanation:

So, I was fired in order to

increase the institute’s work effectivity. It is strange, because I

was under the impression I was quite productive. Notwithstanding the

fact that I was the first researcher to ever receive a GAČR grant at

ÚSTR, in 2016, here are the headlines of the articles I published,

am about to publish, or submitted for publication only in the last

two years (since 2020), all in top international journals or

international academic publications, and keeping in mind that I was

working only part-time at ÚSTR from September 2021 to October 2022.

As it happens, this has probably been the most productive period of

my life:

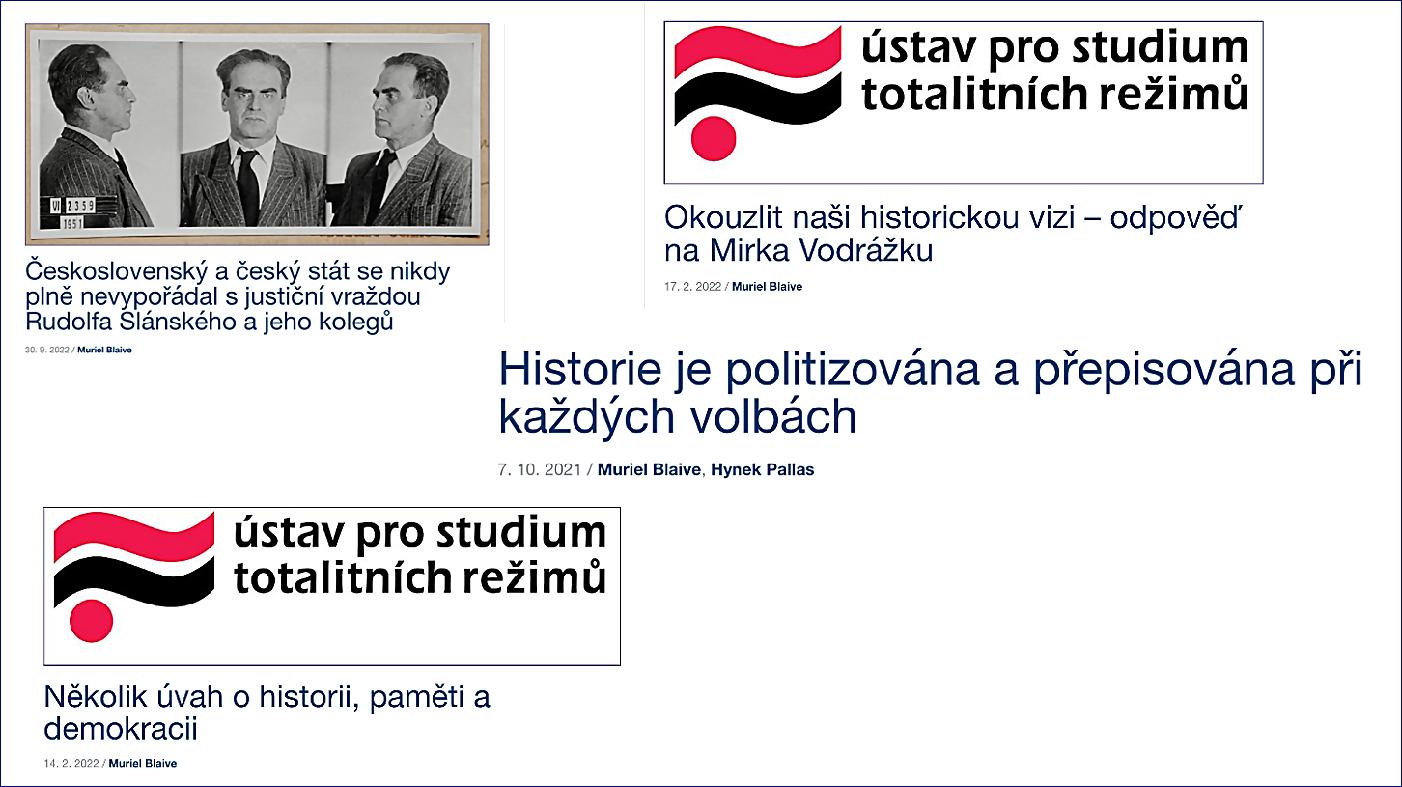

Perhaps my employers thought I

was not engaged enough in the Czech public sphere? But also since

2020 I published not a few articles addressed to the Czech wider

public:

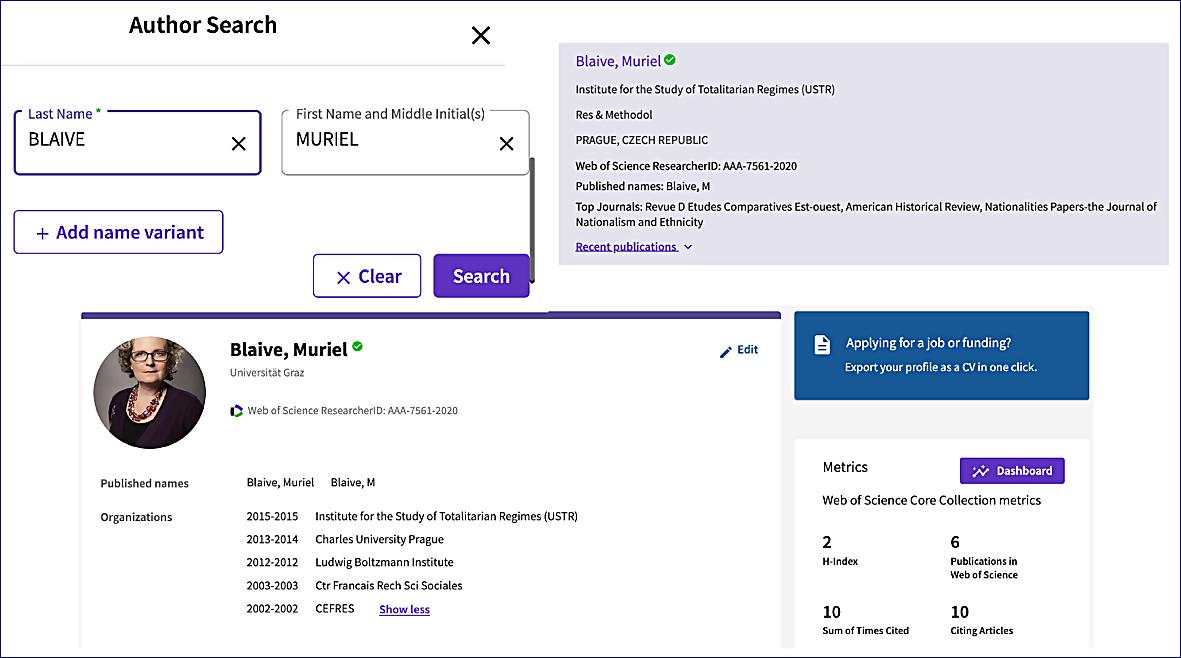

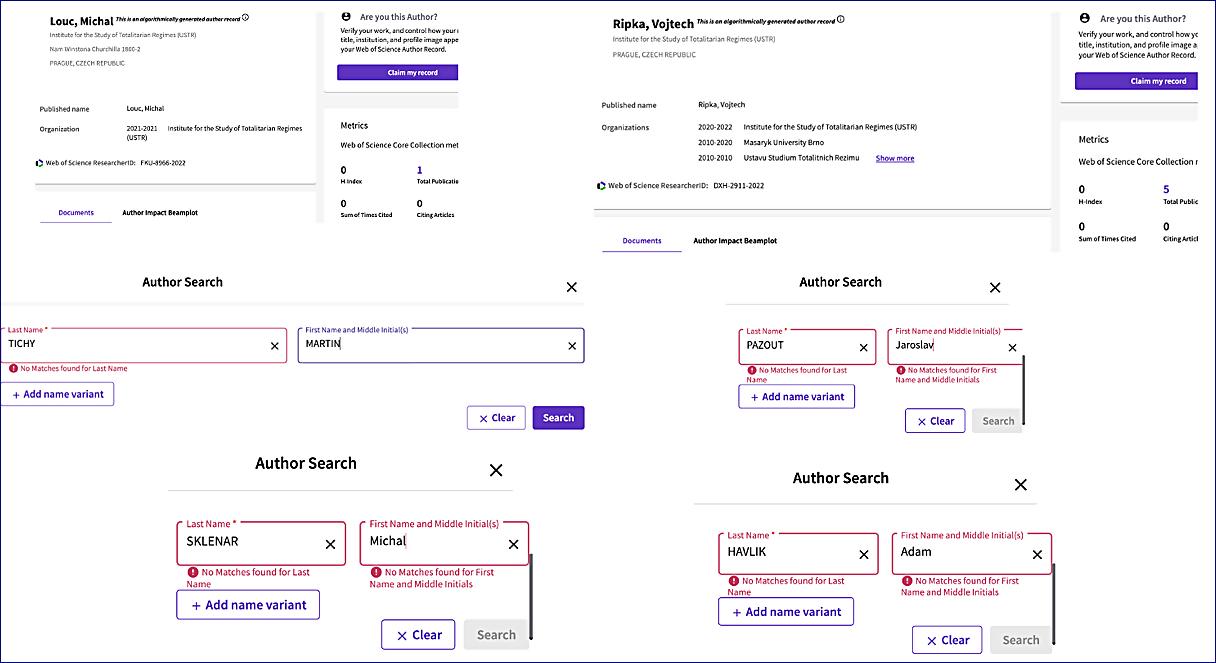

Since neither my academic

publications nor my publications for the wider public appear to be

the problem, I reflected that my employers might have thought I did

not have enough of an international profile, so I checked my status

on Web of Science. Web of Science is an international metric database

that measures the influence of scientists via the references to their

work in other researchers’ publications in impacted peer-reviewed

journals. While I have reserves about its usefulness in social

sciences (it is, as often, conceived for hard sciences), its aim is

to provide an immediately measurable instrument to evaluate

researchers, and it is widely used by universities and research

agencies. The Czech Science Agency (GAČR) uses it, too. Here is my

profile:

My H-index is 2. Is it much?

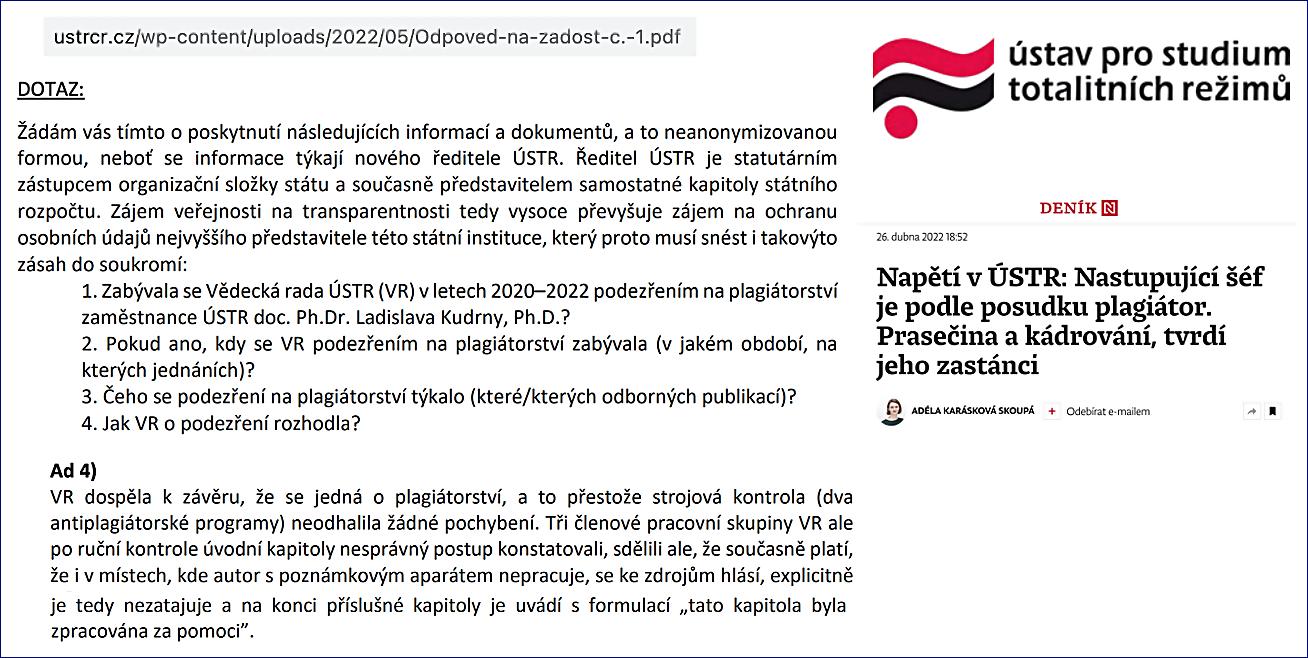

Is it little? Let us compare it with the director of ÚSTR, Ladislav

Kudrna, who is habilitated, which is in theory a higher rank than

mine:

Unfortunately, he is not

indexed, i.e. his record is less than zero and he has no visibility

at all at the international level. But then, international journals

are usually not impressed by plagiarizers, and according to a special

commission nominated within the ÚSTR Scientific Advisory Board that

gave its conclusion in 2021 and was made public in 2022, this is

exactly what Ladislav Kudrna is (which didn’t stop the Board of

ÚSTR from electing him director):

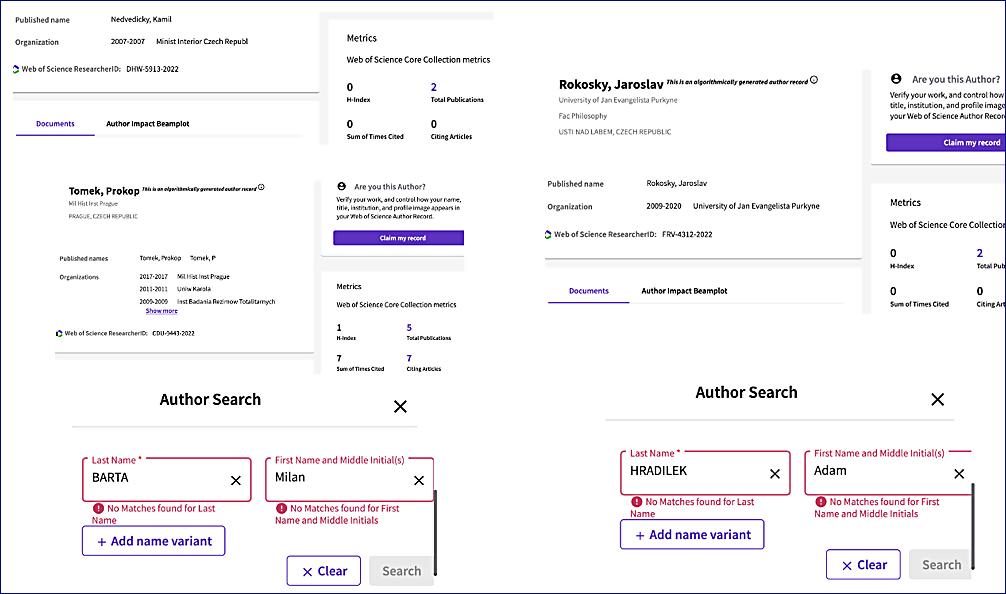

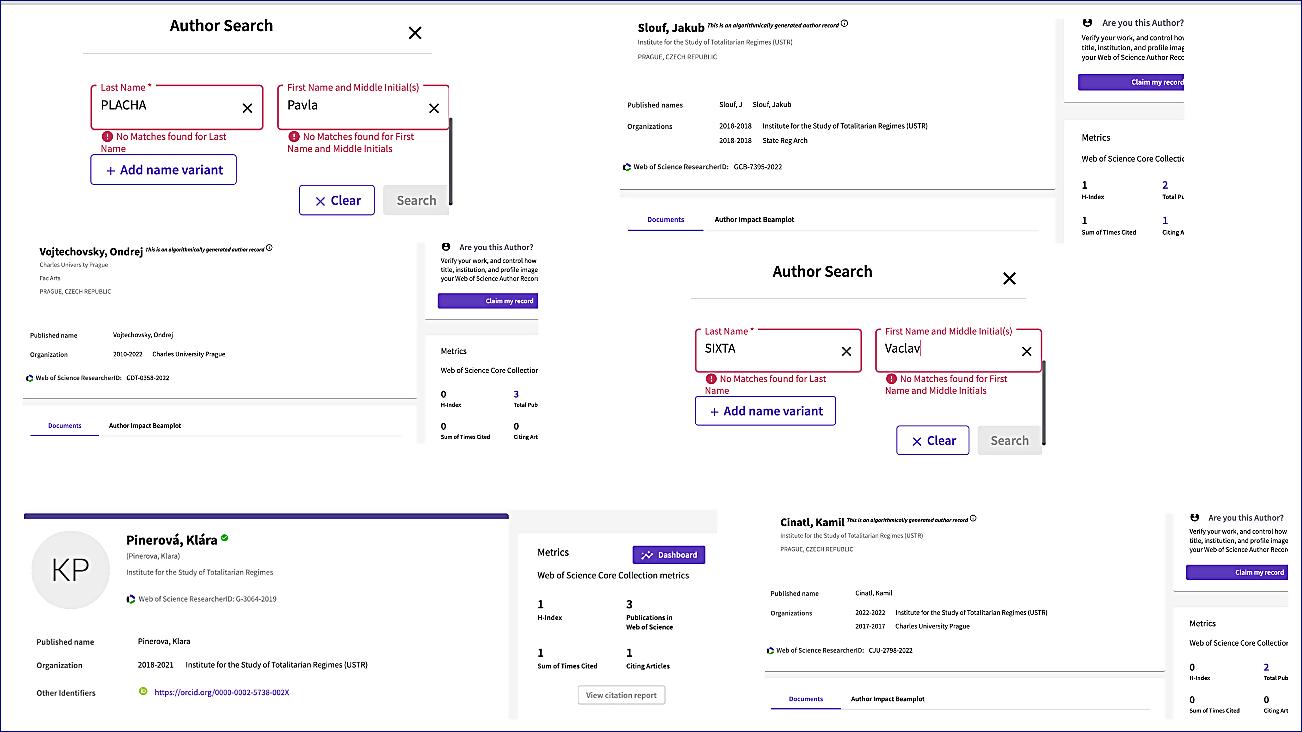

If the director doesn’t have

a record, what about other leading members of the institute? I

checked:

It appears all the men at the

helm of the institute have a lower scientific reputation than mine,

or none at all. I checked on our most famous colleague at ÚSTR, Petr

Blažek. I was impressed that he had an H-Index of 5, until I

realized this is not the same Petr Blažek: this one is a biologist

specialized on agriculture. I didn’t find “our” Petr Blažek in

the database, but this might be a mistake – I also can’t find the

director of the Institute for Contemporary History, Miroslav Vaněk,

although he is widely published in English. Different universities

have different levels of access to the database, so this is perhaps

the explanation.

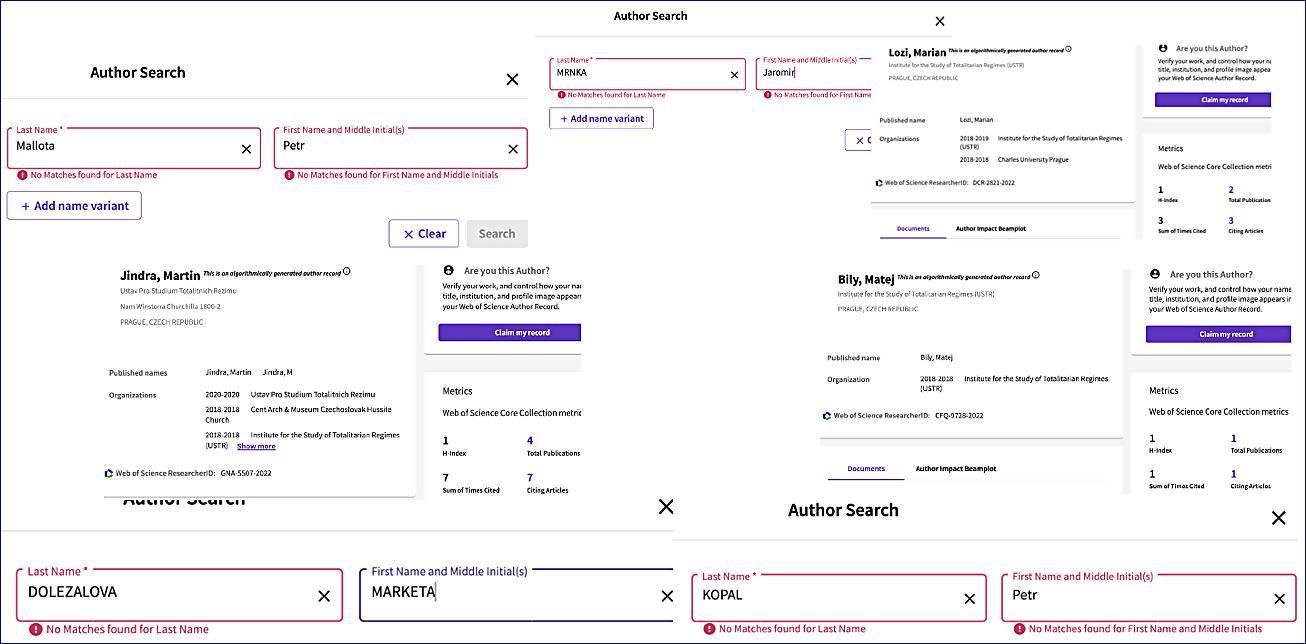

In any case, I then checked

some more of my colleagues at ÚSTR:

I did not check every name.

But from this preliminary search, I seem to be the most published, or

at the very least one of the most published, researchers of the

institute. Let me reiterate that this H-Index might not deserve the

faith research agencies put in it, and it rewards age and experience.

I know for a fact that some of my younger colleagues who are absent

from the database or have a low score are nevertheless excellent

historians. But my point is, if a Czech institution has the good

fortune to hold in its ranks a researcher who has a relatively high

international profile, shouldn’t it aim to keep them rather than

fire them?

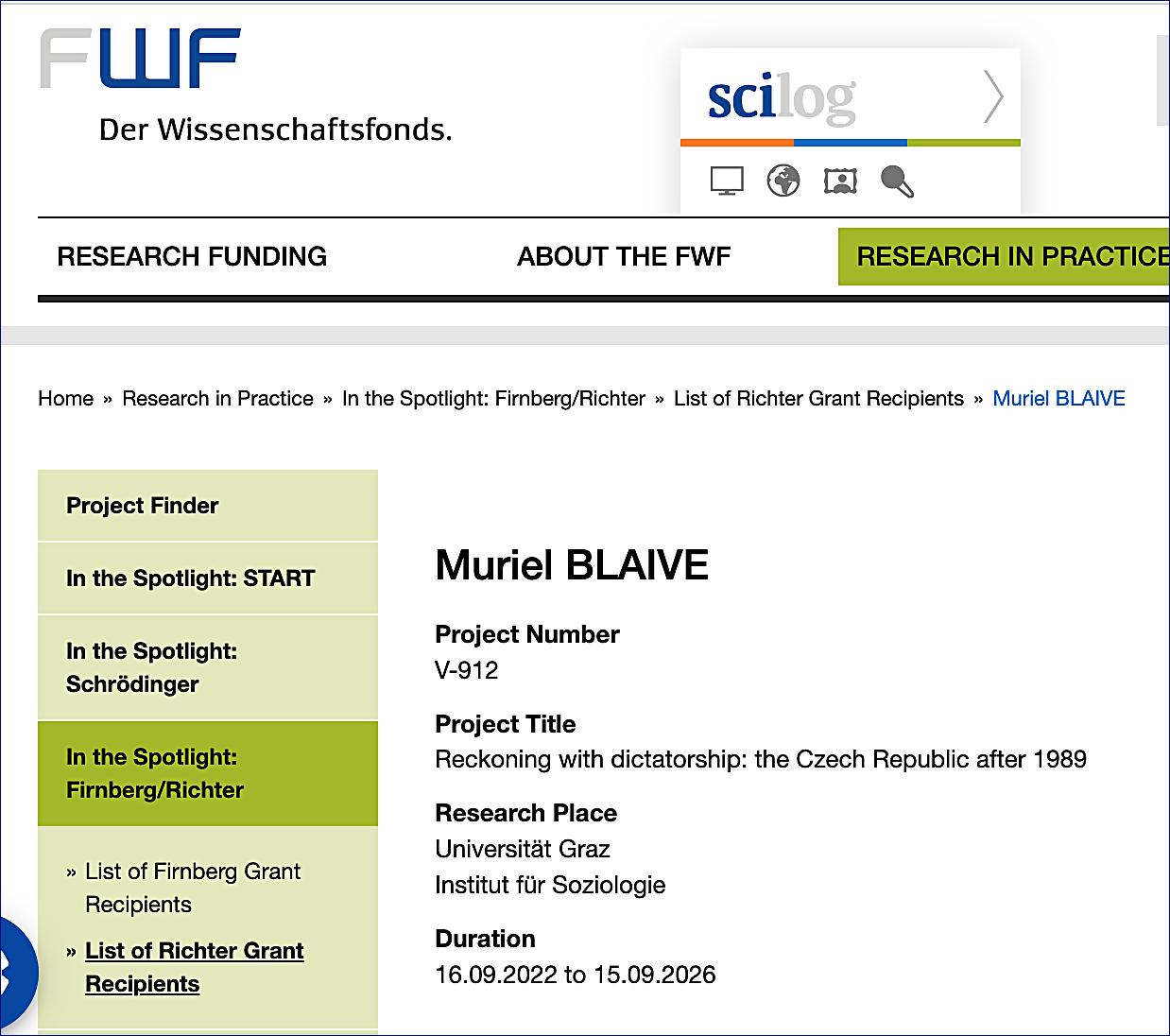

The rest of the world appears

more aware of my value as a researcher than ÚSTR: in 2018-2019 I was

granted a prestigious EU fellowship, the EURIAS, at the Institute for

Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna, as well as an equally prestigious

Marie Curie Senior Fellowship at the University of Aarhus in Denmark

(which I had to turn down since I couldn’t do both fellowships at

once.) In 2020-21 I was granted a Senior Fellowship at the

Internationales Forschungszentrum Kulturwissenschaften also in

Vienna, then in 2022 a four-year Elise Richter Senior Fellowship in

the Department of Sociology at the University of Graz.

My fellowship in Graz was an

ideal opportunity for ÚSTR to engage in an international

cooperation. The Austrian research agency FWF allows me to work for

only five hours a week on top of my full-time fellowship. By working

five hours for ÚSTR (12,5% of a full-time position), I would have

cost the institute a negligeable Kč 6,000 a month (gross), but I would have been able to credit all my international

publications to the institute, and I would have created a

relationship to the University of Graz which could have proved

profitable in the future to both parties. Also, my project appears to

me of great interest for a memory politics institution like ÚSTR: it

is about reckoning with the communist past in the Czech Republic, and

specifically about resorting to the category of crime against

humanity, as Romania now does, to finally punish some of the crimes

committed under the communist regime that went completely unpunished

after 1989.

“We are not interested”, I

was told by the directorship of ÚSTR. “This is not in our

purview.”

Next I offered ÚSTR to do in

these five hours a week the project for which I had earned my senior

Marie Curie fellowship. As the readers of Britské listy will know, I

am not a great supporter of the theory of totalitarianism, but the

instrumentalization of medical power to implement communist

domination on the female body via the medical and social practices of

childbirth is a fascinating case of what even I consider genuine

totalitarianism.

“Women are very interesting,

but we are not interested”, said the directorship again.

I work on little projects here

and there that could easily occupy me five hours a week (recently,

one on Rudolf Slánský, one on an ordinary family who emigrated in

the 1970s, one on the concept of “totalita”, one on Václav

Havel’s essay The

Power of the Powerless,

and I will also soon go back to České Velenice to continue my oral

history study at the border.) But I never got a chance to offer to

work on these projects as I received notification of my being fired

without any further negotiation. Had ÚSTR kept me on board while

demanding that I work more hours, I would have gone back to FWF and

asked for an exemption from the five-hour rule – especially since

the Czech salary I am getting is, from an Austrian point of view,

negligeable: contrary to what Mirek Vodrážka once accused me of, I

was really not in this job for the money. However, it all ended

differently. Director Kudrna had promised the trade unions he would

not fire any researcher, so the trade unions are fulminating; but

then, can one ever trust the word of someone who was proven by an

expert commission to be a plagiarizer?

Since it appears difficult to

justify that my publication record, my international profile, or my

research projects could really hamper the “work productivity” of

the institute, what could possibly be the reason for my being fired?

Journalist Barbora Tachecí of state public radio might have the

answer. She has a limited understanding of my research, but a strong

opinion as to the opportuneness of ÚSTR

hiring me as a researcher.

In March 2022 she interviewed

newly elected director Ladislav Kudrna and had with him the

following exchange concerning my research, which starts at

15’07’’:

In March 2022 she interviewed

newly elected director Ladislav Kudrna and had with him the

following exchange concerning my research, which starts at

15’07’’:

Tachecí: I

can't help it, because that Ms Blaive, who is most famous for her

statement that there was no violence at all during the Communist

Party rule here, but everything was part of a broad agreement between

the population and the state leadership, so this lady was and maybe

still is, I ask you, a collaborator of ÚSTR?

Kudrna: If

I have the correct information she is still an employee of the

Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

Tachecí:

Which you are the head of.

Kudrna: Of

which I am now the head, yes.

Tachecí:

Well, how are you going to deal with this?

Kudrna:

(laughing) How do we deal with it... Well, look, there's no doubt

that my colleague Blaive is an educated woman. She undoubtedly

understands her craft, I have no doubt, but I have no doubt that our vision of the past is vastly different, and I for one ... I don't

want to have statements made on the floor of the Institute that just

don't take its statutory mission into account. That sort of puts us

in a cul-de-sac. (...)

Tachecí:

No, I mean, it's terribly interesting what's considered revisionism

and what's considered fabrications, or untruths, or outright lies, yes?

At what point do you consider statements that evaluate the past in

contradiction to all historical facts to be, in a relatively

conciliatory way, revisionism, and at what point do you say “you're

just a researcher who doesn't stand for anything if you don't base it

on known facts“, do you understand me?

Kudrna: I

understand.

Tachecí:

(...) A mathematician can say, I don't allow anybody here at the

institute who doesn't know that 1 and 1 are 2, and you say, but he

can have the opinion that 1 and 1 are 3, but I don't allow that at

the institute. Do you understand me?

Kudrna: I

understand, I understand (laughter), we understand each other on that

point.

Was I not, in reality, fired

for political reasons? This is what I want to argue in a court of law

since I intend to sue ÚSTR. I have worked and written on the policy

of dealing with the communist past in the Czech Republic since 2002,

i.e. for exactly twenty years. I have quipped during the last

election of the ÚSTR director, for which I applied, but my

application was discarded on technical grounds, that I was the only

one among the candidates who actually cared about history, and the

same could probably be said about the previous election in 2014. I

could not be less interested in Czech politics, and/or in positions

of power or prestige. I only want to do my job as a historian.

Indeed I care greatly about

history. Why? Because one of the very first persons I met in Prague

was a woman who had been threatened by the StB and blackmailed on

account of her children, and after 1989 she saw this StB agent pursue

his career without the least impediment. In 1996 I read Josef

Škvorecký’s novel Two

Murders in my Double Life,

in which he describes the ordeal experienced by his wife, novelist

and publisher Zdena Salivarová, after she was accused of being on

the Cilbulka list of collaborators – she won her trial, but not

before being heartbroken. Over the years I witnessed multiple

scandals in Czech (but also Polish, German, and Hungarian) public

life and was also made privy to heartrending private stories of

injustice in dealing with the communist past, either because people

were wrongly accused of being collaborators, or because the communist

officials who had ruined their lives never had to account for their

actions after 1989. I led oral history interviews and listened to

ordinary Czechs angrily recount the level of asset-stripping and

corruption, and the rise of social inequalities, that accompanied the

so-called transition to democracy. I saw this country squander its

egalitarian heritage and plunge into historic levels of individualism

and selfishness, not only leaving behind an impoverished part of its

population but endangering, because of the level of popular anger

that this resulted in, the European Union that I have always

supported.

Because identity is so

intimately linked to history in this part of Europe, historians can

and should have much to say about memory politics. Contrary to many,

I remain convinced that ÚSTR was very much needed as an institution

and has a strong cohesive role to play within Czech society. What I

have had to witness, deconstruct, and write about so far,

unfortunately, is rather the instrumentalization of the communist

past for present political purposes that have nothing to do with

history, and even less so with the well-being of the Czech

population. And just like the ordinary Czechs I regularly interview,

I don’t like hypocrisy.

9289

In March 2022 she interviewed

newly elected director Ladislav Kudrna and had with him the

following exchange concerning my research, which starts at

15’07’’:

Diskuse